Sat. 15th June 1991

There are only thirteen of us on this trip, mostly older people, travelling in twos and threes. We board a coach at the back of the Central Station in Amsterdam, which takes us to Brussels Airport where we board the Aeroflot plane for Leningrad. Surprisingly, there are no seats at the back reserved for smokers, you can smoke anywhere in the plane. Besides our party, the other passengers are grey-suited Russian 'diplomats' (party members?). We arrive at the ramshackle international airport building in Leningrad, pass through passport control and a cursory customs check, and then have to wait around 20 minutes or so before our 'hostess' arrives with the coach to take us to the hotel. On the way we learn that the hotel is 8 kilometres from the city centre.

The hotel, called the Pulkovskaya, is a huge modern building on one side of Victory Square, overlooking the monument to the soldiers who died defending Leningrad during World War II. It's a typical Western-style hotel, a 'joint venture' operated with Western 'know-how'. My room on the 6th floor is indistinguishable from any other 'Western' type of business hotel: single bed, TV, noisy air conditioning, but at least there's a refrigerator, so I can have ice with the whisky I'd bought at Brussels airport. After taking a rest I go down to join the rest of our group for dinner. The restaurant area is, by Russian standards, quite luxurious - there's even, it seems, provision for a stage show, with spotlights and a disco ball, but the food is very basic - two pieces of boiled meat and some greasy rice. After dinner I attempt to change money at the hotel bank, but they've just run out of receipts. This puts me in a quandary: since I donÕt have any Russian money I can't take the metro into the city centre as planned. I try to change money unofficially at the hotel reception, but they won't do it. It occurs to me later that the official tourist rate of 27 rubles to the dollar just doesn't make it worthwhile for Russians to sell rubles on the black market.

So I go back to my room and take another short rest and then start phoning some of the numbers Bas had given me back in Holland, of artists with whom I should get in contact. I reach the filmmaker/photographer Evgeni Yufit and arrange to meet him on Monday. Yufit gives me some other names to call. One of them, Yurat Filkul, speaks hardly any English. He keeps saying, 'I speak very, very, very bad English', so our conversation is limited, to say the least. I manage to reach another artist, Valerij Marozov, and make an appointment to meet him the next day at the entrance to the Academiskaya metro station. Both Yufit and Marozov are members of the Leningrad Necrorealist group, which is the group I am most interested in finding out more about. As soon as I put the phone down, the calls start coming in. It seems that Yufit has spread the word that there's a Western critic/curator interested in organising an exhibition in Holland, and suddenly everyone starts calling me. The critic Victor Mazin, who does speak good English, gives me some more names and useful information about current exhibitions. Inbetween calls, I decide to go for a short walk. It's 10 p.m. and still light outside, so I take a stroll up the Moscow Prospect to see how far the nearest Metro station is. It's not far, about 10 minutes walk. Most of this part of the Moscow Prospect is flanked by a huge department store (huge in length rather than height - above the ground floor are what look like ordinary apartments), whose windows are noticeably lacking in produce. The window displays have a 50s, institutional look to them.Sunday 16th June

In the morning I go with the group on a guided coach tour of Leningrad. It's a huge, spacious city with many buildings in the old city centre dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. The oldest buildings are painted ochre red and white, others are green or blue and white. Most of the buildings survived the siege during the 2nd World War, but the ravages of time (and neglect) have caused several to fall into disrepair. Many appear to be in a slow (sometimes up to 30 years) process of restoration, such as the beautiful church built on the spot where one of the Czars was assassinated. We stop to admire the view from the Naval Training School and are beset by begging women and children, who are shooed away by the ever-present police. We take a look around the cruiser 'Aurora' which had fired the shot that signalled the start of the October Revolution. Below decks there's a museum of memorabilia, where I take a few photos. On the way back to the hotel we pass several buildings which appear to be empty and decrepit.

Lunch at the hotel (boiled meat again!) and then I make my way to the Metro for my appointment with Valerij Morozov. Valerij is waiting for me, as arranged, at the entrance to the Metro, together with a small child and a woman who introduced herself to me as Ilena, an art critic. We take a bus to Valerij's small apartment, which he shares with his parents. We sit in a sparsely furnished room, two of whose walls are covered with 4 paintings on paper by Valerij, all depicting the same image of a grimacing, monstrous-looking male head.

I am immediately offered vodka, and we sit drinking and talking. Ilena speaks better English than Valerij and acts as interpreter. Valerij shows me the Stedelijk Museum catalogue, and I begin to sort out who is still a member of the Necrorealists group and who not. I explain my plan to arrange a photography/film show, but it seems that Yufit is the only artist in the group who is involved with photography. Perhaps a concurrent show can be organised in Rotterdam of the group's paintings and sculptures. Valerij gives me a small plaster sculpture of one of his totem-like heads. I take some photos of Valerij and his works and we leave to go to see some of his sculptures that are in a building somewhere. We take an (unofficial) taxi and drop Ilena and her child off on the way. The building is an exhibition space, where Valerij works part-time installing shows - at the moment there's a show by the American graphic artist Peter Max. On the staircase, apparently in storage, are two groups of Valerij's wooden sculptures - the same grimacing head roughly carved out of different types of wood. A small framed statement explains that the wood was acquired near the graveyard where 'violently killed homosexualists' are buried.

Valerij wants to show me another gallery, so we take a taxi, but find out that it's closed. It's now about 7 p.m. and we're both hungry, so we head for the Nevski Prospect, where we find a co-operative restaurant. The waitress doesn't want to let us in, but Valerij bribes her with 10 rubles and we're given seats. Along with the meal (meat and potatoes) we drink a half bottle of cognac, by the end of which I'm beginning to get rather drunk. We're sitting right in front of the restaurant's entertainer - a singer with an electronic keyboard, who regales the diners with old Beatles songs and Russian standards. After the meal we head off in yet another taxi to visit some of Valerij's artist friends. We arrive at a building in a semi state of ruin, somewhat like the squatted houses that artists live in in Holland and England. Valerij bangs on various doors and we eventually find some people at home. The scene is like some parody of Bohemian life - four or five people are seated around a rickety table drinking cognac. Our host - a jovial, bearded painter already in an advanced state of drunkenness - proudly displays his latest creation on a easel - a painting of a woman against a lurid background. Quite awful. Other paintings crowd the walls in various styles and subjects, including city views. The sort of 3rd rate tourist art that one sees in places like Montmartre in Paris. I can't resist taking a photo of the painter posing with a couple of his canvasses.

After 15 minutes or so, Valerij and I excuse ourselves and go off to visit another friend. On the way Valerij decides to buy some bottles of wine, so we head off in another taxi in search of what would appear to be difficult-to-obtain merchandise. Valerij stops the taxi 2 or 3 times to get out and consult with knots of people standing on street corners. Eventually he returns carrying 4 bottles of Baltic wine and we head for his friend's apartment. Four or five other people are there too, crowded into a room about 2 by 4 metres. We start drinking the heavy, sweet wine, and our host passes around a joint. It turns out that he's a filmmaker and he has made a half hour 16mm film. I persuade him to show it, so he pins a sheet to the door, and positions the projector. The film is in black and white and seems mostly to consist of shots of young people fooling around, views from a car travelling through the city and bits of hand-applied scratching and animation. A lot of it seems to have been shot at slow speed, so the projection is very jerky and fast. I notice that the projector has no take-up reel and that the film is spewing out into a tangled heap on the floor.

Whether it's the film, or my befuddled state of mind resulting from the combination of vodka, cognac, wine and dope, but halfway into the film I start feeling extremely bad. I try to concentrate on deep breathing, but I'm starting to get nauseous. I excuse myself and head for the toilet, where it absolutely reeks of shit and piss. I retch a couple of times and stand for a while leaning against the wall. After a few minutes someone comes and brings me a stool to sit on in the corridor, and after a while I feel better. We watch the rest of the film, and then, as it's around 12 at night, I decide it's time to get back to the hotel. Valerij and I stumble out into the street. As we stand waiting for a taxi, our host comes running out and gives Valerij a passionate kiss. Valerij explains to that the'Õre lovers, or at any rate that our host is, as Valerij puts it, 'his woman.' IÕm not sure what to make of this, but a taxi eventually pulls up and is willing to take me back to the hotel for a dollar. Back at the hotel, I crash out on the bed in my clothes and sleep until 4 in the morning, then get undressed and sleep until 9.15. I've missed breakfast with the group, but fortunately I can buy a breakfast at the buffet for 10 rubles.Monday 17th June

I decide to stay sober today, phone Igor Brizikov and arrange to meet him the next day. After shaving, and writing part of this diary, I set off around noon to take the Metro to the Russian Museum. The entrance to the museum is via an inconspicuous basement door. Once inside, I see signs in English directing visitors to the collection of 19th century Russian art, so I wander around, but the paintings on show are completely uninteresting. Upstairs, there are old Russian icons to be seen. I'm looking in vain for the 20th century section (as mentioned in the guidebook), so I ask a guard who directs me to another wing of the museum. Eventually I find the entrance, and there is indeed a small collection of works from the 1920s and 30s - a few interesting works by Popova and Goncharova, but in general most of the paintings on display are fairly uninspiring. ThereÕs also a show of 'underground' Moscow art from the 60s and 70s but, apart from some pieces by Komar & Melamid and Kabakov, these are pretty dismal works - abstract, both formal and informal, a sort of 50s Parisian style. Maybe for Moscow audiences in the 60s these works might have been scandalous, but to me they look dated and 2nd rate.

I head back to the Nevski Prospect and go into the 'House of Books', a two-storey bookshop, but find that it is stocked exclusively with books in Russian. I browse through the posters on sale, but find nothing to interest me. In this shop (as in the Museum) there seems to be an all-pervading odour of cat piss.

Everywhere along the Nevski Prospect there are knots of people clustered around stalls where someone's selling pastries or cheap perfume or 2nd hand books. I'm feeling hungry so I buy 3 cakes for one-and-a-half rubles. At about 3.30 I take the Metro to go to Ilena's apartment where I'm supposed to be meeting Yufit. I arrive promptly at 4, and a few minutes later Yufit and his scriptwriter arrive, followed a little later by Valerij. I explain to Yufit the idea of an exhibition in Rotterdam. He says little, but listens carefully. He tells me that he will only have new works ready in October. Since he's the only member of the group who makes photoworks, it looks like his show at Perspektief will have to be a solo one, with other Necrorealist works (paintings and sculpture) possibly shown at some other place in Rotterdam. I'll have to talk to Thomas Meyer about this when I get back.

I give Yufit two empty video cassettes so he can make copies of his films for me to take back to Holland. Ilena has to leave, but says she will be back soon to take me to see another photographer. Yufit, the scriptwriter and Valerij leave, so I'm left alone with a young man called Radion, with whom I discuss politics, culture, economics, etc. for a while. I'm beginning to get bored with the discussion and by 7 Ilena still hasn't come back, so Radion gets a taxi and takes me to Usov the photographer. Usov is a traditional photographer. He takes pictures of rock stars, Caucasian landscapes, street scenes. He shows me all his prints, one by one. I'm afraid I'm not very enthusiastic about his work, and our conversation is limited by the fact that he only speaks French. All the while his young son is demanding attention, trying to grab the prints, etc., but Usov is remarkably patient. The conversation drags on painfully, and by 9 I'm beginning to wonder what's happened to Radion, who's supposed to be picking me up to go back to Ilena's, from where Ilena and I are supposed to go to someone's house to make a copy of parts of the NR films in which she appears. At about 9.30 Radion arrives at Usov's and we make a speedy departure by taxi back to Ilena's, and then Ilena and I walk to the house of a film producer who fortunately has 2 video recorders.

This is my first viewing of the Necrorealist films - they seem indeed inspired by the Bunuel of Le Chien Andalou, and look a little like the European and American Happenings of the 60s. Also on the tape is a film (or video) showing the shooting of a TV film about the Necrorealists two years ago. The TV film was recorded in the kitchen of a communal apartment in Leningrad and shows Yufit in the process of filming the other members of the group who are lying and crawling on the ground in various states of dress and undress, covered with sticky goo, interspersed with (attempted) interviews with the group and with Ilena who is standing on the sidelines watching.. Next we see the actual TV documentary itself, which deals with the history of the group and shows fragments of their films (including the kitchen 'happening'). Also included are interviews with an outraged public after a showing of their films and, most remarkable of all, comments by psychiatrists on certain of the more 'scandalous' scenes in the NR films. Ilena, it seems, has been very active as a member of the NR group, as well as an independent curator and critic. Another section that she tapes while we're at the producer's apartment is an interview with her about the show she organised devoted to Russian rock music.

Then we see some examples of the film producer's own work - a couple of very conventional documentaries about two towns in northern Russia, showing local handicrafts, the renovation of the church, etc., accompanied by an American-accented commentary. Akatov (the producer) asks me if I think there would be interest in Holland in his work, but I have to tell him that he could better aim at America, particularly the American-Russian 'friendship societies' (representatives of whom I'd seen at the hotel a couple of days ago). Then he shows me another film about what he calls 'anecdotes'. This is really remarkable - it opens with a scene in a madhouse, whose straight-jacketed inmates are immediately recognisable as Marx, Lenin, Breznev, etc. Unfortunately it's getting too late to see the whole film, so I arrange to meet Akatov the next day to give him an empty video cassette so he can tape a copy for me.

I walk Ilena back to her apartment. It's now 1.30 and I have to make sure I get a taxi before 2, otherwise the bridges will be open. I quickly exchange addresses with Ilena (she's leaving the next day to spend a few days at her dacha with her son), and Radion comes with me to hail a taxi. Eventually we find one and I'm back at the hotel around 2.30.Tuesday 18th June

Up at 9. There's no sign of the Dutch group, so I breakfast at the buffet. Then I go back to my room, and take a nap as I'm feeling rather tired. No hot water for a bath, so I write my diary, and take it easy. I take lunch at the buffet, and notice a girl in her early 20s sitting opposite me. After a while she's approached by a Finnish man and after exchanging a few words, they disappear together. It dawns on me that she's a prostitute, servicing one of the many Finnish men who come to Leningrad for cheap sex.

I take the Metro for my appointment with Igor Brizukov, arriving at his apartment around 2.45. Brizukov used to be a member of the Necrorealists and had been included in the Stedelijk exhibition, but now he's left the group (or been thrown out) and is working on his own as a painter and filmmaker. He's a pleasant giant of a man and lives in a house where almost every room seems to be an artist's studio (but without the clutter that characterised the studios Valerij took me to on my first day). I learned later that many of these large houses are owned by the Mafia who are hoping to renovate them and rent them out to rich businessmen - in the meantime they let artists use them. I take slides of Brizukov's paintings. It seems that he's having difficulty finding his own direction after leaving the Necrorealists. His work is mostly semi-figurative and doesn't appeal to me very much. We go upstairs to visit some other artists - a photographer who shows me 50 or so small black and white toned prints (mostly portraits) and another photographer, a woman, who also does portraits but in a somewhat more interesting way. I tell her about the Rijksacademy and she's interested so I give her a copy of the Academy brochure, warning her that the selection process is very competitive [I later meet her in Amsterdam and she actually does manage to get accepted at the Rijksacademy]. In the same apartment there's another artist working, Victor Snessar, who's made whole installations in two of the rooms. His work is much more conceptual and humorous, using painted words on aluminium. He's already shown in Germany. Interesting work, somewhat in the direction of Kabakov, and very well made. While we sit drinking tea with the others, he shows me some of his photoworks - documents of performances in which he dresses up as a 19th century literary figure reading aloud in the street, or as a 19th century 'holy fool' making a performance in the snow, which includes the ritual burning of his own clothes and of a pseudo-Constructivist painting bearing the word 'nihilism'.

ItÕs time for me to leave as I have to meet Valerij at the Central Exhibition hall (where he works), so he can give me the tape Yufit made of his films. After meeting Valerij (briefly going with him to his 'studio' nearby where he's working on another of his wooden totem heads), I head off in search of the main telephone exchange with the intention of phoning Claudia, but when I get there I see there's a queue 30 metres long and no information in English, so I give up and head down the Nevsky Prospect in search of the 2nd hand bookshops Ilena had told me about. I pop into a few other shops on the way, just to see what's on sale, but in every one of them there's a long queue, just to buy a jar of conserved fruit or butter or pastries. I find one interesting 2nd hand bookshop, but it's nearly 7 p.m. and about to close.

I've got an hour before I'm supposed to meet Akatov outside the Gorkovskaja Metro station (to give him an empty cassette to record his 'anecdotes' film), so I take the Metro from Mayakovsky station to the Finland Station. This was the station that Lenin arrived at in 1917 after his journey in the sealed train from Switzerland. It's now called Lenin Station and there's a big, imposing statue of Lenin outside. Inside there seems to be nothing to commemorate the events of 1917 - it's just an ordinary railway station.

I take a token photograph of a blank, painted wall, and then walk along the river and across the bridge towards Gorkovskaja, arriving there about 8.15. Akatov is there waiting. I give him the tape, but decline going to his apartment as I'm feeling tired and footsore, so I arrange to meet him at the same time and place the next day to receive the video, and wearily take the Metro back to the hotel. Luckily I find our Dutch group still sitting at dinner (they're quite surprised to see me!), so I eat and then go to my room, take a bath, and write this diary (until now: 11.50). Then read a bit and go to sleep.

Wednesday 19th June

This morning the group is going in a guided tour of the Hermitage, and I decide to join them, which is just as well, since when we arrive there we find a long queue outside the entrance, but our guide is able to whisk us through. Had I gone on my own, as I'd originally intended, I'd have had to spend ages queuing. The Hermitage adjoins, and is part of, the Winter Palace, so I see what the Soviets were storming in 1917! There's an impressive collection of Rembrandts (more than in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam) and all the other important Dutch old masters, as well as Renaissance Italian and French paintings. Upstairs there's two large rooms full of Picassos, a Matisse room, Bonnard, Van Gogh, Cezanne, etc. Alas I could find no Manets.

Back to the hotel for a late lunch, then take a rest for an hour or so. Pretty soon itÕs time for an early dinner, after whichI take the Metro to meet Akatov to pick up the video. Having accomplished that, I take the Metro one stop to Nevsky Prospect and go to visit the videomaker Juris. He shows me bits and pieces of his videos - some interesting shots of a disco, edited in-camera, somewhat like MTV. He also does a sort of magazine programme called Pirate TV. Juris has travelled in recent years to France and Holland and is contact with people like Nam June Paik, but he doesn't consider himself a 'video artist'. His concerns are more directed towards TV and video collage. I arrange to see him again to get some copies of his videos. Maybe Time Based Arts would be interested in his work, I tell him. By now it's about 11, so I head back to the hotel. Write the above, and read a little.Thursday 20th June

Up at 8.30, and join the group for breakfast. Decide not to go with them to some palace or other, but take the subway to Nevsky Prospect in order to visit the Lenin Museum. On Nevsky Prospect I find a shop with a sign in the window saying that they sell 'old postcards', so I have a look. Besides postcards, they also have 19th century photographs, stereo cards, etc., as well as a marvellous set of Magic Lantern slides, which I buy - the whole package only comes to 49 rubles (less than $2).

I walk the short distance to the Lenin Museum, which turns out to be mostly full of documents, photos, books, etc. There's nobody else there, apart from a couple of dour female security guards, who don't object to my taking a few photographs (particularly of the displays). Nearby is the departure pier for the jet-foil to Petrodvorets, so I buy a ticket for 3 rubles and queue for half an hour to get on. The trip takes about 30 minutes. It's another of the Czar's palaces, built on the model of Versailles. Unfortunately it's raining so I wander around for an hour or so and then take the jet-foil back to the Hermitage. Go back to the old postcard shop and but a stereo viewer and set of glass plates (118 rubles for the lot). Back to the hotel for dinner with the group.

Valerij phones, arrange to meet him the next day. Try in vain to contact Mazov and Tchekin.Friday 21st June

Dreamt in the night about Documenta - I was there with Claudia - many of the works on show were the same pieces as shown at the last Documenta. In one section there were some pieces by Duchamp, which were almost hidden - you had to lift up wooden flaps to see them. In a corner an artist (Bob Lens) was dressed up in 18th century costume and seemed to be obsessively playing with some objects on the wall. There was a member of the public who was being deliberately argumentative and trying to pick fights with people - this turned out to be a performance - I recognised the man as being Bruce MacLean. Met Pieter L. Mol. Claudia had gotten angry with this fake violence and had walked away. I chased after her. By now the scene had changed to a department store. I was looking for Claudia among the aisles.

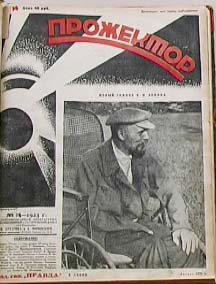

Up at 8.30. Breakfast with the group. Take Metro to Nevsky Prospect and return to the second-hand bookshop where I had spotted an old bound volume of a Soviet magazine. I ask to have a closer look at it, and it turns out to be very interesting, containing many photos of Soviet life in 1923. I buy it for 250 rubles.

From Mayakovsky Station I take the Metro to Gorkovskaya and visit the Museum of the Revolution - quite a dreary building, with an unkempt front garden. Pompous displays of photos and documents, and furnishings (e.g. the desks, phones, etc. used in the Revolutionary Council offices). I take a few photos, and go and sit on the steps outside and leaf through the book I'd just bought. To my great surprise and pleasure, I find reproduced the (original) full page images of the boy and girl Young Leninists that I'd used for my piece 'Corpus' (and which Lissitsky based his famous poster on).

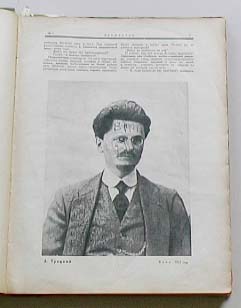

Metro back to Nevsky and walk to the Central Exhibition Hall to meet Valerij. He gives me a letter to post from Holland. I suggest going for a drink somewhere, but the nearest place is closed, so we end up walking all the way along Nevsky (maybe 6 or 7 hundred metres) to another place. Here they only sell large glasses of cognac, which is apparently what Valerij wants. He downs two glasses, while I only take a half. In the meantime I get him to translate a few words and names from the Soviet magazine, and I realise that there's some genuine Cubist and Constructivist stuff in it, as well as a remarkable article on the Soviet version of US Taylorism. All the photographs and drawings of Trotsky, I notice, have been crudely crossed out in pencil, and the words 'class enemy' added. After Stalin's coup, I learned later, all Soviet citizens were required to deface images of Trotsky (and other 'undesirables') in this way.

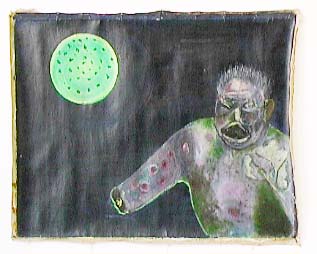

I wanted to buy an 8mm film projector, which I'd seen in a shop on sale for the equivalent of $10. I explain to Valerij that I have to get back to the hotel to change money so I can buy it, but within a few minutes he's managed to change 10 dollars into 270 rubles, so we go and buy the projector. It's now about 6.30 - too late to get back to the hotel for dinner with the group, but there's still the buffet dinner, so I invite Valerij to join me. We take the Metro. After dinner Valerij tells me that he wants to make me a gift of a graphic by him, and asks if I would come to his house to pick it up. But I protest that I'm too tired and have to get to bed early anyway. So Valerij says he will go home himself and bring the graphic back to the hotel. After about an hour and a half he's back, carrying not only the graphic, but also a rolled up painting. The graphic is not so interesting, and the painting is in Necrorealist style - a cosmonaut looking at the moon. He wants to sell me the painting. I ask how much. $35. I think about it - I'm not really very crazy about the work, but Valerij has been very kind and helpful during my stay in Leningrad, and $35 is really very little to pay for an original painting. So I buy it.

It's now nearly 11 and I'm feeling very tired, so after one more drink in the hotel 'night bar', where there seem to be several prostitutes hanging around, I bid farewell to Valerij, take a bath and at last get to bed.

Saturday 22nd June

Up at 5.30, quick breakfast with the group in the snack bar, then board the coach to go to the airport. I disguise the painting inside a poster roll, but the Customs discover the bound set of Soviet magazines and say that, since it's more than 50 years old, it's not allowed to be taken out the country. I manage to persuade them that I need it for academic research, and eventually they let me keep it.